“Caveful of Clues About Early

Humans”

Interbreeding With Neanderthals Among Theories Being Explored

Interbreeding With Neanderthals Among Theories Being Explored

- September 20, 2004; Page A06

See text of paper below.

| ||

Caveful of Clues About Early Humans

By Fredric Heeren

Special to The Washington Post

“Field research” projects

often require scientists to endure discomfort and danger to get

where they need to be, but not many can trump this

summer’s expedition to what may be the world’s most

inaccessible human fossil site, a cave in the foothills of

Romania’s Carpathian Mountains.

For the seven-member team, the hazards of

reaching the site, accessible only by diving through frigid

underwater passages, were worth it. Their finds may help answer

some of the most hotly debated questions about early humans:

Did they make love or war with Neanderthals? Were Neanderthals

intellectually inferior to our human ancestors?

This may be asking a lot of the scanty

fossil remains of three individuals who lived 35,000 years ago,

but their age makes them the earliest modern humans ever found

in Europe. The uniqueness of the site, which was discovered in

2002, was motivation enough for the specially trained team to

devote a month of cold and dangerous underground journeys to

reach and excavate the site known as Pestera cu Oase -- Cave

with Bones.

The team included a Portuguese shipwreck

diver and archaeologist, a French Neanderthal specialist, a

Romanian cave biologist, and the three Romanian adventurers who

discovered the human fossils while exploring submerged caves.

At the start of each day’s nine-hour

excursion underground, team members stepped into a frigid

mountain river that flows into a cave, their helmet-mounted

lights piercing the perpetual fog of the cave’s 100

percent humidity. As the equipment-laden crew sloshed past

stalagmites, the cave narrowed and the air temperature plunged

from the 90s to the upper 40s Fahrenheit.

Further in, the ceiling lowered until they

were forced, first, to swim on their backs and, finally, don

their diving masks and enter a narrow, 80-foot-long underwater

passage called “the sump.” Underwater visibility

was about three feet.

Lead diver Stefan Milota warned newcomers:

“Do you know how long it takes to die in the sump?

Twenty, thirty seconds and you’re gone.”

When Milota first told biologist Oana

Moldovan in 2002 that he had found a human jaw in a closed-off

chamber, Moldovan wanted to see for herself -- even though she

had to learn to dive to do it.

“I had to see the cave,” said

Moldovan, now the team’s project coordinator. “So I

was very motivated. But I was very scared. My first time, it

was horrible.”

Surfacing inside another chamber, the

divers peeled off their wetsuits and changed into warm

clothing. The next step was climbing “the pit,” a

series of underground cliff faces that the cavers scaled in

dizzying climbs up a succession of ladders they had carried in

earlier.

Finally, to reach the gallery of bones,

they passed through “the gate,” an opening that

Milota had first spotted when he felt warmer air emerging. He

and his explorer friends widened it just enough for the

thinnest of them to squeeze through. Each day, the cavers had

to plunge head-and-arms first at a slight uphill angle, then

wriggle and rest, wriggle and rest, to cover the final, winding

10 feet.

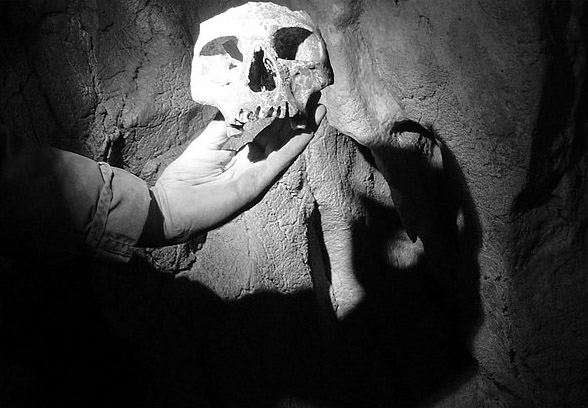

Inside the final gallery, there was room

for only three workers at a time because the rest of the floor

was covered with thousands of fragile fossils. Most belonged to

a cave bear species that became extinct 10,000 years ago --

animals almost twice as big as today’s bears.

The original entrance caved in long ago,

sealing off the galleries from the outside. After two labs

independently yielded radiocarbon dates of about 35,000 years

for the jaw, or mandible, that Milota had found, more

scientists took interest. In a 2003 expedition, they found a

full face and an ear region of a skull from two more

individuals, with puzzling traits that suggested a mix of

Neanderthal and human features, something scientists had

thought impossible.

Anthropologist Erik Trinkaus of Washington

University in St. Louis and Joao Zilhao of Cidade University in

Lisbon joined this summer’s excavation to look for more

specimens and to try to find out how the human remains got into

the cave. Because they turned up no sign of torches, charcoal

or tools, they concluded that the human remains had washed in

through fissures.

The biggest payoff of the summer was the

discovery of more fragments of the three individuals found

earlier, which added to the evidence of hybrid traits.

Trinkaus said the Oase fossils show

features of modern humans: projecting chin, no brow ridge, a

high and rounded brain case. But they also have clear archaic

features that place them outside the range of variation for

modern humans: a huge face, a large crest of bone behind the

ear and enormous teeth that get even larger toward the back.

Trinkaus made a CT scan of the face to

measure the unerupted teeth. “To find wisdom teeth that

big,” he said, “you have to go back 500,000

years.”

The team considered whether early humans

might have interbred with other hominids with Neanderthal-like

features, but “in this time period,” said Trinkaus,

“the only archaic humans those modern humans could have

interbred with were Neanderthals.” The mosaic of

Neanderthal and modern traits remind Trinkaus and Zilhao of

similar traits they found in a 25,000-year-old fossil of a

child in Portugal.

Researchers pondering why the Neanderthals

died out have speculated that early humans might have killed

them off, and Zilhao said the signs of interbreeding do not

exclude that possibility. “We know that even when people

fight, the winner might kill the males and keep the females

from the other side,” he said.

The signs of interbreeding challenge the

standard wisdom that Neanderthals were a distinct, less

intelligent species.

“If you look at the archaeological

evidence,” argued Trinkaus, “which includes things

like burials, there is very little difference between what we

find associated with Neanderthals and what we find associated

with early modern humans -- from the same time period.”

Richard Klein of Stanford University

thinks this holds true only until about 50,000 years ago, when

modern human behavior changed dramatically. “There could

have been interbreeding,” Klein conceded. “But all

the genetic evidence we have suggests that, if it occurred, it

was remarkably rare.”

Six years ago, Zilhao and Francesco

d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux published evidence

that Neanderthals independently invented and used personal

ornamentation. Zilhao said these finds have changed the view

that Neanderthals were an inferior species.

Klein said the picture is changing, but

not in that direction. The real question today, he said, is

“whether modern humans fully replaced the Neanderthals or

simply swamped them” genetically, with greater numbers.

“And it may never be possible to say.”

* * *